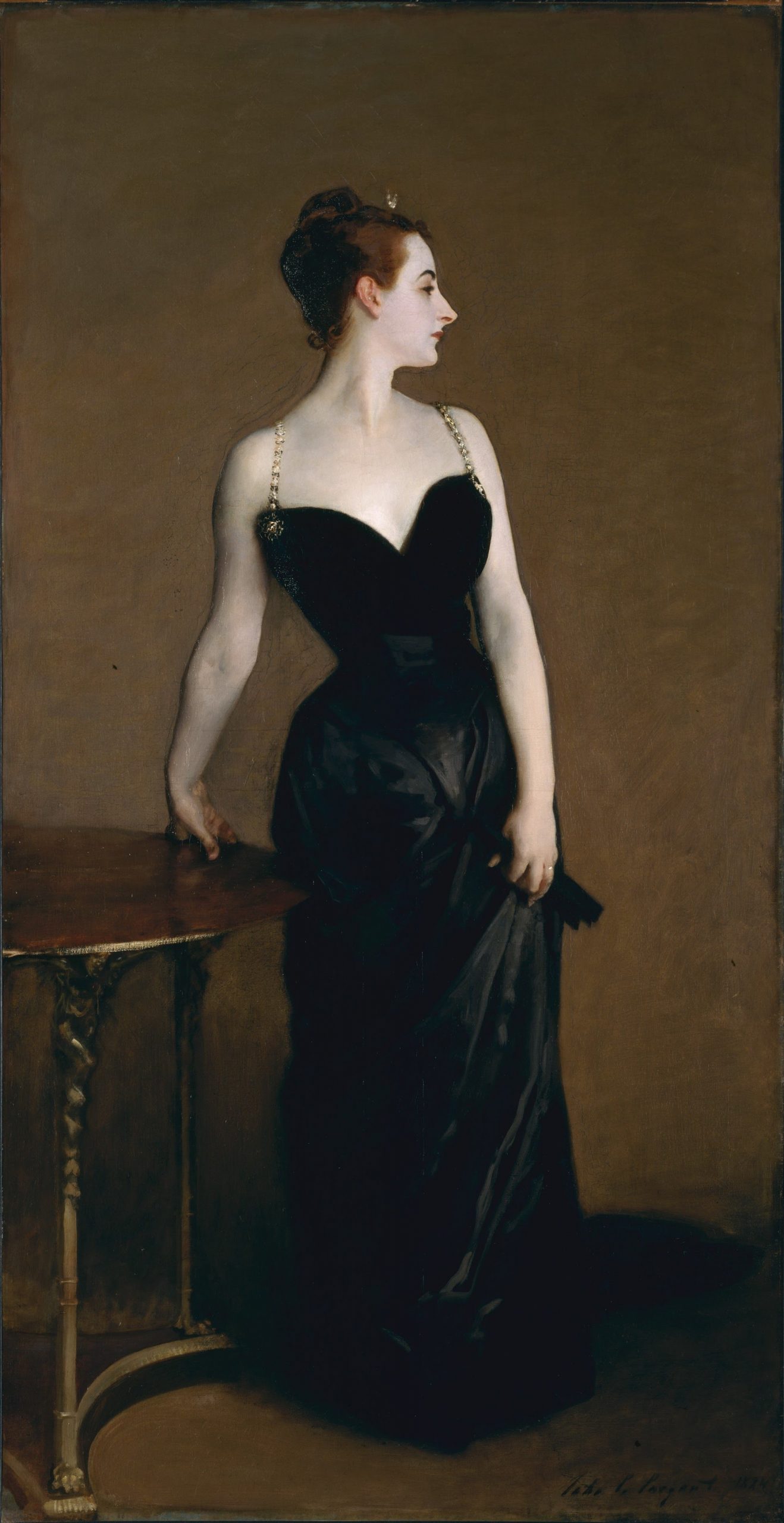

Let’s talk about Madame X. I am not talking about Madonna’s album of a few years back but this amazing portrait by John Singer Sargent.

John Singer Sargent, Madame X, 1883–84, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It’s so striking! That’s partly because of the contrast between the model’s pale, flawless skin and the sumptuous black gown she’s wearing but the clean lines of her silhouette against a very neutral background also help. The background was originally, by the way, painted in blues and greens but Sargent wasn’t happy with it and he re-painted it after the image was in the frame; bits of the original blue can be seen round the edges.

So who is Madame X and how did she get to have such amazing skin?

Madame X was Madame Pierre Gautreau an American living in Paris who was renowned for her beauty and panache. Her skin is so gorgeous because a) she’s only in her early 20s and b) she used a powder made of potato starch to cover her skin. I have also read that she used to consume arsenic to make her pale but this is unlikely to be true.

Anyway, loads of artists wanted to paint her but she generally said no, perhaps because she knew she would hate being still for a such a long time? Sargent was to find that out.

After pursuing her for a couple of years telling her what an incredibly talented artist he was, and how his painting her portrait would be the making of them both, she sat for him – but not for long. She was restless, she then demanded months off and the whole thing turned into a bit of a nightmare and then got a whole lot worse.

The portrait was accepted at the Paris Salon in 1884 where artists were still either made or completely undone. His portrait which was originally entitled Madame XXX a convention to maintain her anonymity rather than a statement about its sex rating, was absolutely vilified. Critics said that she was a caricature and looked like a corpse but moreover, the xxx might as well have stood for the sex rating because she was seen as essentially as a prostitute. What we would see today as the poise and sensuality of a confident woman was cause for outrage and scandal in late 19th century society.

It didn’t help that the strap of her gown was originally falling off her right shoulder (Sargent later repainted it), which jarred with the wedding ring on her left hand. Nor that she is wearing an unusual tiara that could be equated to the goddess of the hunt, Diana.

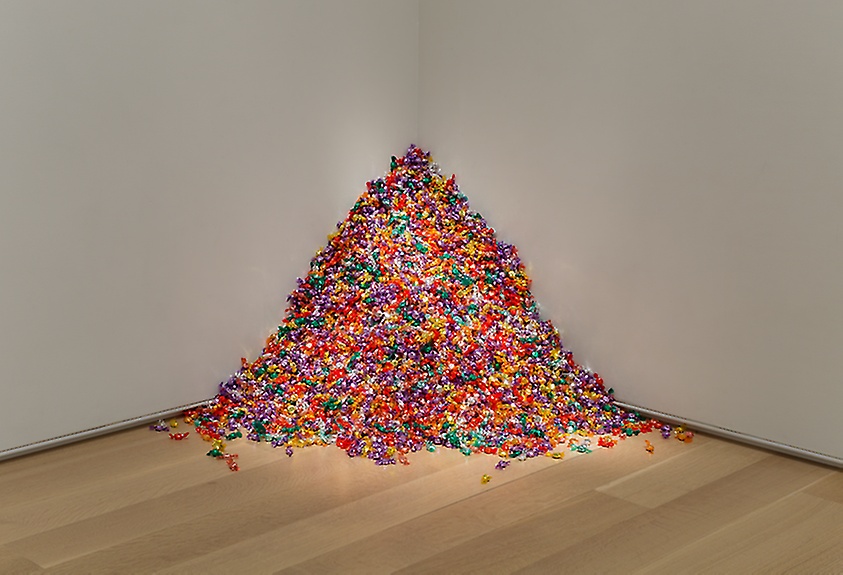

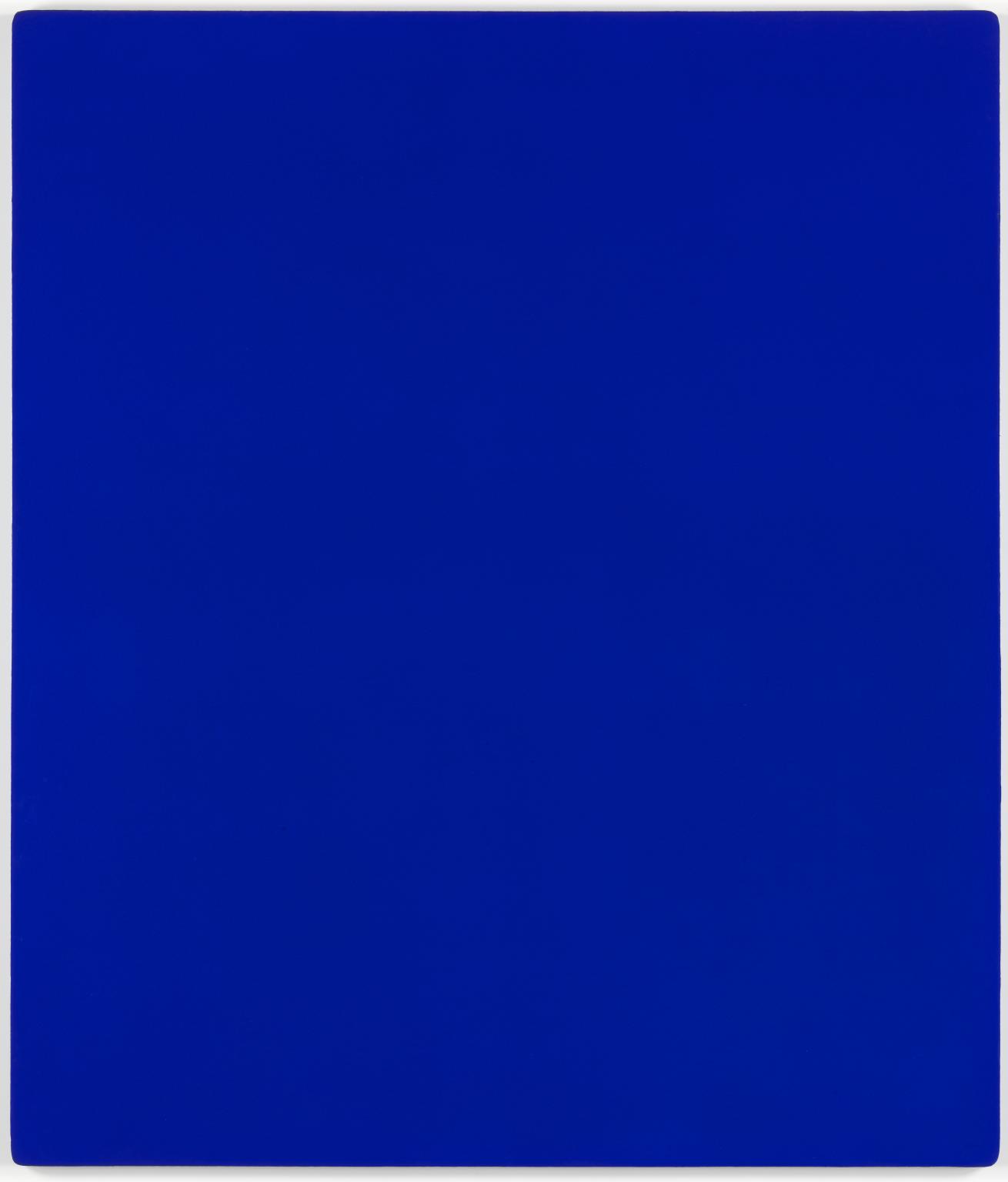

Detail of Sargent’s Madame X, 1884, Met, NY

Detail of Titian’s Diana and Actaeon, 1556-59, National Gallery, London

Diana, as depicted in Titian’s wonderful Diana and Actaeon, is a chaste goddess who has the moon as one of her symbols; check out her headdress which is the same as the one Madame X is wearing. Fine. But if you transfer the idea of hunting under the moonlight to the context of Parisian high society, you could get a different idea.

Mme Pierre Gautreau or Virginie Amélie Avegno as she was before she married a wealthy banker more than 20 years her senior, did, perhaps, have a wild side shall we say? She was also the ‘it’ girl of the age but all that stopped after the Salon.

Her mum, who seems to have been a bit pushy and probably orchestrated the marriage and perhaps the portrait, hoping for more fame, was horrified when the reception of the work was less than warm and demanded that the painting be removed from the salon, claiming that her poor daughter might die of chagrin. She didn’t die of chagrin but her image was tainted irreparably. Some of the more dramatic stories about her claim that she took all the mirrors off her wall and would only go out at night. I’d doubt the veracity of this as she subsequently commissioned another couple of portraits but she never regained her former status.

John Singer Sargent in his Paris studio, ca. 1883–4. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Sargent suffered from the fallout of the Salon too. He had been banking on the portrait being a hit and securing commissions. He hadn’t been paid for this one because it was only at his request that Virginie sat for him. So it was a bit of a disaster all round. He fled the country and came to London and kept the portrait for 30 years until a year after her death in 1915, he sold it to the Met. He wrote to one of the museum’s curators: “I should prefer, on account of the row I had with the lady years ago, that the picture should not be called by her name.” Hence it is now displayed as Madame X. He also commented, “I suppose it is the best thing I have done,”. It’s quite a portrait.

The video of this episode can be viewed here. To view the entire ‘Elevenses with Lynne’ archive, head to the Free Art Videos page.

Recent Comments