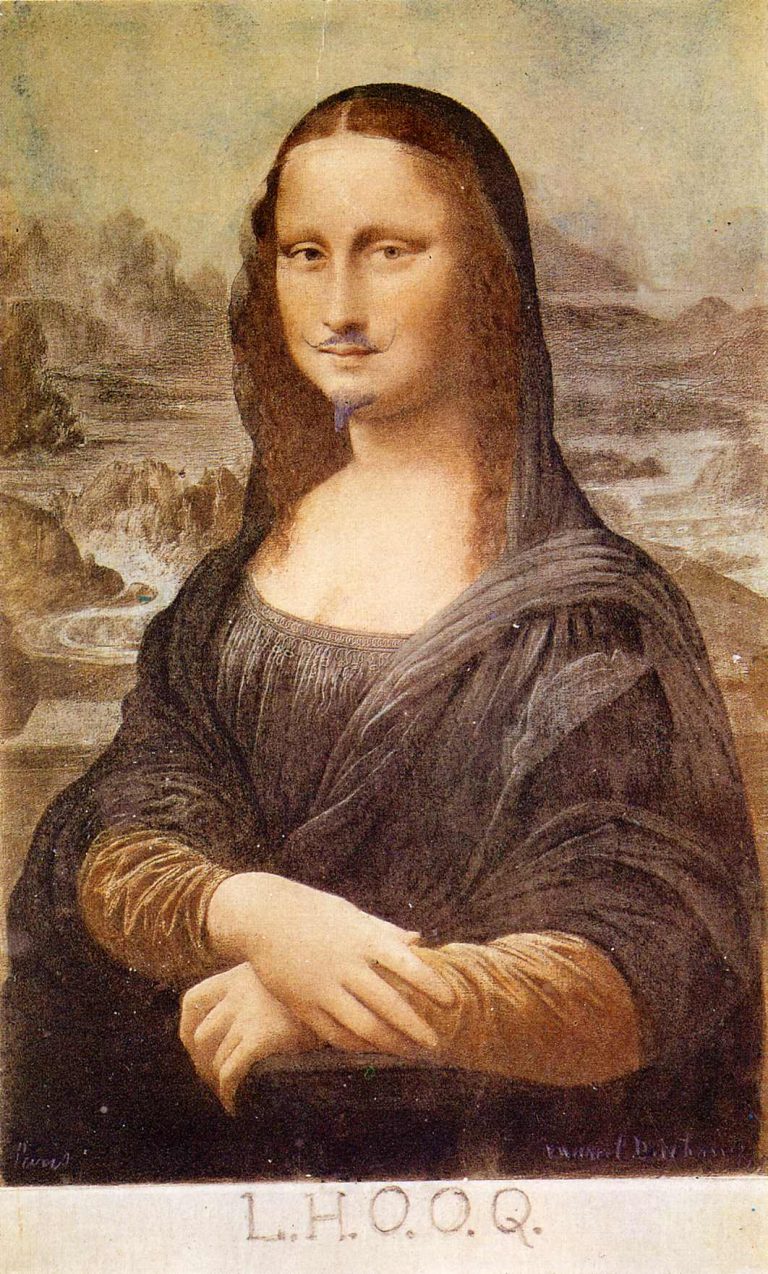

Marcel Duchamp is perhaps most famous for submitting a urinal signed R. Mutt for display in an exhibition in 1917 but this work comes hot on its heels. A cheap reproduction of the Mona Lisa complete with a scribbled in moustache and a goatee and the letters L.H.O.O.Q written beneath it.

Marcel Duchamp, reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa with added moustache, goatee, and title, 1919, Private Collection, Paris

What does it mean???

Firstly, Duchamp was playing with phonetics; when you read the letters quickly in French it sounds as though you are saying ‘elle a chaud au cul’ or to translate, ‘she’s got a hot arse’, although Duchamp himself gave a loose translation as ‘she’s got a fire down below’.

There are several ways that this can be interpreted.

- The feminist reading

‘She’s got a hot arse’, or ‘she’s got a fire down below’ are undeniably sexual comments that invite allusions to the male gaze which isn’t great. It empowers men and objectifies women. Women are reduced to becoming the passive objects of a man’s desire. So the poor Mona Lisa is a dignified woman who is now merely reduced to a sex object.

But that doesn’t really account for the moustache and goatee.

- The school boy reading

Duchamp’s work does often have more than a whiff of the playground about it. It’s such a juvenile thing to do to whack facial hair on a sedate lady – he did this in pencil but then added some word play which is admittedly pretty witty. The thing is that then Duchamp passed the work off as an original work of art. He called these works objets trouvés or found objects; basically every day things that he modified in some way. So, yes, playful and silly but there’s thoughtful intent behind his actions… so not totally school boy.

- The anti-establishment reading

Let’s just talk about the fact that he chose to ‘enhance’ a postcard of the most famous painting in the world. He may have had his friend Apollinaire in mind when he chose the Mona Lisa. Apollinaire had wrongly been accused of having a connection to the theft of the painting in 1911 but was later acquitted.

Whatever his motive for selecting this work, he’s taking the world renowned masterpiece down a peg or two. He’s poking fun at something sacred! That’s no slight to the lady herself but more of an insult to the madness of the art world and to the swarming masses who blindly worship certain works because it’s the done thing. He’s also, I think, making a little point about the merit – or not – of cheap reproductions.

That would be quite a reasonable reading of LHOOQ but there’s more.

- The Freudian reading

With her moustache and beard the Mona Lisa looks more than a little masculine. Duchamp argued that she doesn’t become a woman disguised as a man here but that she actually becomes man. Freud had something to say on the subject of the original work declaring that he believed da Vinci to be homosexual (what a bombshell!!!!) and that there is always male within his portraits of women because he couldn’t identify with the feminine. Essentially their femininity was a flimsy veneer. At the very least he was working with androgyny mused Freud. So, Voila! Who knew that the Mona Lisa was actually a man until Duchamp stuck a moustache on her?!

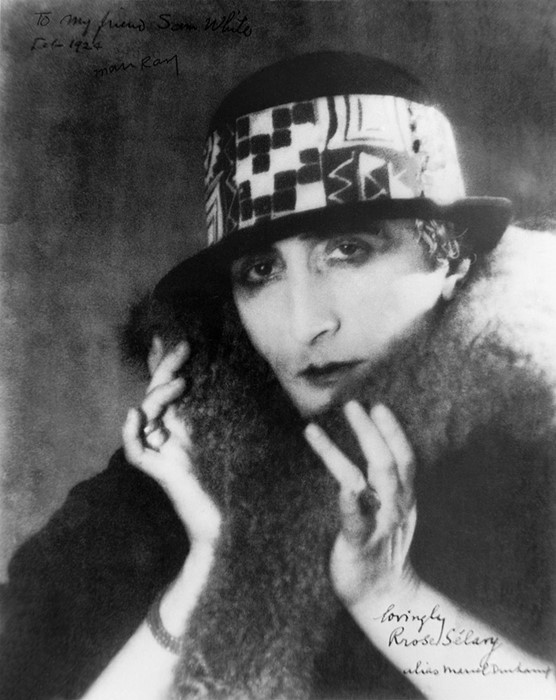

Duchamp did like playing with gender. He had an alter-ego called Rrose Sélavy, pronouced ‘Eros, c’est la vie’ (‘Eros, that’s life’). I think this was more about exploring ideas of identity and representation than trying to trick anyone or illicit cheap thrills.

Rrose Selavy (Marcel Duchamp), 1920© Man Ray Trust/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015

Whatever his motive in choosing the Mona Lisa, Duchamp was probably aiming, rather successfully as it happens, to pick apart and challenge everything that art represents. Actually, he dedicated a career to that. With this work he’s also elevating a banal reproduction to something that others wanted to copy in their own right. Duchamp himself also made several replicas, including one that he adapted from his friend Picabia who was so eager to publish a version in his magazine that he knocked a version out himself forgetting the beard. Duchamp later added the goatee and labelled it ‘Moustache par Picabia / barbiche par Marcel Duchamp / avril 1942’.

The video of this episode can be viewed here. To view the entire ‘Elevenses with Lynne’ archive, head to the Free Art Videos page.

Recent Comments