Gazing into the glazed eyes of Michelanagelo’s Bacchus in the Bargello in Florence a few years ago, a friend said to me that you kind of have to love him, even if he looks a bit dodgy. Unusually, I couldn’t quite agree. I was more with the poet Percy Shelley who wrote that the god of wine looks ‘drunken, brutal, and narrow-minded, and has an expression of dissoluteness the most revolting’. A virtuoso piece of sculpting though.

Michelangelo, Bacchus, 1496-7, Bargello, Florence

Michelangelo’s Bacchus can barely focus on his cup and he definitely looks as though he could sway off that marble podium at any time. His tummy is protruding, shoulders slumped, and whilst there is evidence of some firm musculature beneath that naked torso, his body appears softly rounded, and somewhat feminine.

His left hand loosely grips an animal pelt, quite probably that of a leopard as they traditionally pulled his chariot, and bunch of grapes that are being slyly nibbled by the little satyr sitting on the tree stump behind him. The pay-off is that Bacchus is practically leaning against the satyr for support. You can practically smell the wine on his breath and see the red stained lips and teeth.

At some point he also made the sartorial decision to adorn his head with vine leaves and little bunches of grapes which resemble curls. If you’ve read the Elevenses blog ‘The art of the Bacchanal’ you’ll know that ivy was more commonly used as Bacchus’s crown. It was supposed to act as a defence against drunkenness. Could have been helpful here?!

Standing a little over two metres high, he is in fact, the embodiment of drunkenness. I haven’t tried, but I imagine wobbliness is pretty bloody hard to achieve in marble.

Which begs the question: who commissioned this and did they actually want a pissed up Bacchus with a slightly sleezy air or something less challenging – after all Bacchus here is a nasty reminder of the effects of drink.

The first question is easy to answer. The consensus is that Michelangelo was commissioned by Cardinal Riario in Rome and began working on the statue in 1496.

The answer to the second question is less clear because we don’t have the paperwork detailing the commission. Regular payments were made but as far as all the evidence suggests, the statue was never actually delivered to the Cardinal but instead displayed in the sculpture garden of Riario’s banker and Michelangelo’s friend, Jacopo Galli.

One theory is that the drunkenness was a problem. This is way past the ruddy cheeked conviviality of many other depictions of Bacchus. Alcohol was the pathway to hell and so it was unseemly in the extreme to have a statue, albeit of the god of wine, that appeared to represent total inebriation, especially if you were a man of the cloth.

Or perhaps it wasn’t quite antique enough. The 16th century saw a lot of excavation and everyone was mad for the statues of classical antiquity.

Michelangelo had just pulled off a magnificent stunt in which he created a marble cupid, roughed it up a bit, and allowed it to be passed off as a genuine antique. This is, in fact, how he met Cardinal Riario who bought the piece believing it to be antique. When he found out that it was merely a fabulous fake, he was initially furious but, once he had his money back, he recognised the extraordinary talent of Michelangelo and invited him to come to Rome. This is when he commissioned Bacchus.

It would definitely seem that Michelangelo was attempting a similar outcome with Bacchus as he did with Cupid (now lost). Word on the street was that the artist himself mutilated the statue to make it look more antique, knocking off the raised hand and cup and chiselling away the penis (ouch).

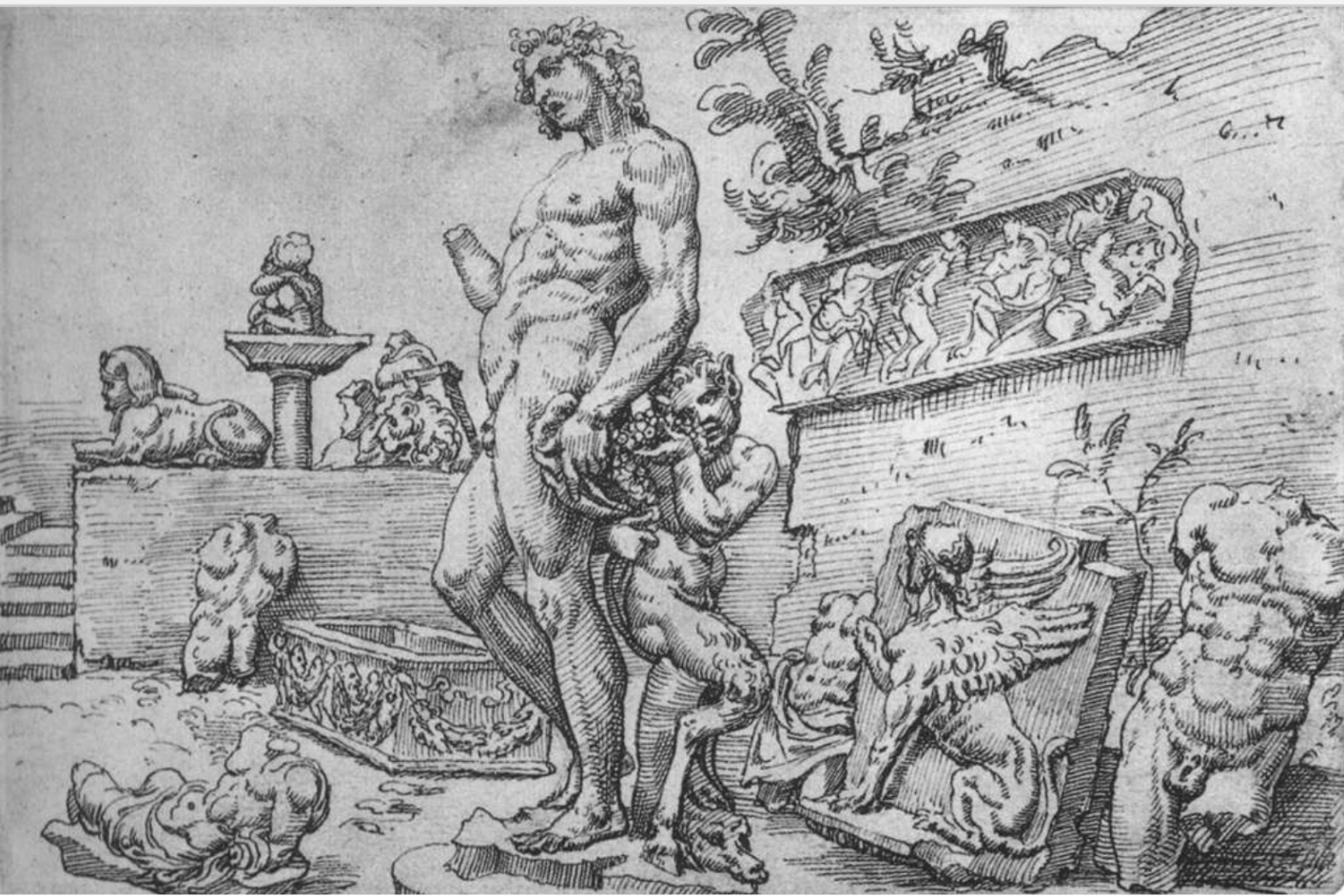

In this sketch by Marten van Heemskerck of Bacchus in Galli’s sculpture garden, dated to the 1530s, you can see that both are already missing. By the 1550s, however, the hand had returned, reattached by the artist using cement, but the penis was never in evidence.

Drawing of Bacchus in the sculpture garden of Jacopo Galli by Maarten van Heemskerck, c. 1533–1536

Did it look antique? Some contemporary commentators definitely thought so, others weren’t sure. Perhaps the slightest doubt wasn’t good enough for either Michelangelo or Riario? Perhaps it just wasn’t the kind of antique Riario was looking for.

Finally, there’s the fact that it may have been considered too effeminate. The issue was that this led to suggestions of homosexuality. Which was forbidden. But rife. Michelangelo was probably gay. Nevertheless you couldn’t promote it in a statue in the late 15th century.

So drunk, not antique enough, too effeminate? All of the above? Who knows?

Michelangelo I imagine was somewhat upset at the time. But for us today, it’s testament to his daring and genius. Would I want Michelangelo’s Bacchus in my garden though? Definitely not.

And the big (or little) question is: where’s his penis?

The video of this episode can be viewed here. To view the entire ‘Elevenses with Lynne’ archive, head to the Free Art Videos page.

Recent Comments