The art of the Bacchanal? Yes, the spotlight for this week’s Elevenses is on Dionysus or Bacchus as the Roman’s called him.

If the Greeks were fond of the slightly obscure and nuanced story of Hephaestus and how wine facilitated a reconciliation between him and his mother (see last week’s post and video), the Romans were more straightforward.

One of their favourite depictions was the drinking contest between Bacchus and Hercules (or Dionysus and Heracles if you’re thinking Greek). Here they are on a very fancy 23-karat gold bowl which was part of an extraordinary 18th century find when a house in Rennes was demolished.

Bacchus & Hercules (detail), Roman gold offering bowl, ca. 210 A.D. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Bacchus is in the centre crowned with ivy (not vine leaves as is often mistakenly stated). Ivy was supposed to defend against drunkenness and at one point the berries were even thought to be a hangover cure (maybe because they’re poisonous and make you vomit?).

[The link between Bacchus and ivy, by the way, made its way over to England where old English Taverns would display ivy above their doors indicating the high quality of their drinks. I would say that self praise is no praise at all but it obviously worked so what do I know?]

But back to Bacchus. He carries a drinking horn in one hand and a staff or thyrsus in the other. The thyrsus usually has an acorn on top (as it does here) or sometimes it’s covered in grapes, vine leaves or ivy and is generally thought to symbolise fertility, hedonism, prosperity – all the good things in life! Speaking of all the good things in life, everyone needs a panther ready to pull their chariot – there he is just below Bacchus, and what is life without good music? Nothing, I’d say so there’s an aulos player to the left, and a panpipe player on the right with a few maenads thrown in for good measure. Although Bacchus is in the centre, the other protagonist on this plate is the muscle man, Hercules, to the right. He’s still standing for now, but the way that he holds out his empty bowl to Bacchus suggests that everything might be about to go horribly wrong for him.

I might suggest that this image is the pair of them a few hours later. This is a pavement mosaic of the same scene, one of five that decorated a dining room in a 2nd century Roman villa. Dionysus is, dare I say it, possibly slightly unfocussed, but he’s finished his cup whilst Hercules, in an Herculean effort, is still downing his wine – remember that you had to drink the same amount at the same speed. Symposium rules applied to the gods, too.

I’m very glad to see that flute girl is back – unusually wearing more clothes than the men. The older chap to the right is Silenus, Bacchus’s great friend and teacher. The child in the centre is Ampelus (a child personifying the vine) who looks, in fact, as though he is clapping Bacchus thus crowning him the victor, at least of this round. Who knows whether that’s the end or not???

Mosaic from Antioch, The drinking contest between Heracles and Dionysus, 2nd century A.D., Worcester Art Museum, Worcester

What we do know is that Bacchus is always going to be the winner because this is an allegorical victory of wine over physical strength. The Romans loved this story (albeit one that they possibly made up as it doesn’t feature in Greek art or literature) and used it, as these two examples show, in diverse mediums.

I suppose at the end of the day the Greek tale of Hephaestus actually tells a very similar story but at least they dressed it up a bit!

Now, speaking of dressing up, or down(!), there are some other figures who are often depicted with Bacchus and I want to end by talking about them.

Say hello to the maenads.

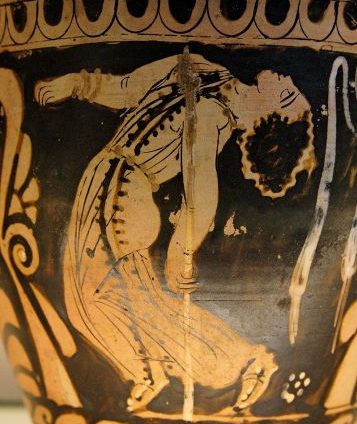

Dancing maenad, detail from a Paestan red-figure skyphos, ca. 330-320 B.C., British Museum, London

Here’s one who’s being very dramatic on the side of a drinking cup and I think the only thing holding her up is a thyrsus.

Who were maenads? Well, they were mortal women who were made mad in the service of Bacchus – maenad literally means madness or frenzy. Many stories suggest that this all happened against their will. Did it? I’ll tell you their duties and you can decide.

Most of their work focused around maintaining grape vines, harvesting grapes, and preparing wine.

Chiusi Painter, Attic black-figure cup depicting sileni and maenads collecting the harvest, late 6th century, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

But when the time came for a Bacchanal or a Dionysian cult ritual, the craziness was ramped up to the max. Think lots of drinking, energetic dancing to exhaustion, more drinking, stripping off and dancing naked, more drinking, orgies, more drinking – all to the point where you believe that you have been possessed by Dionysus himself.

Once possessed, you were connected to the divine because Dionysus was of course a god. So it was an unusual way to seek a religious experience perhaps, but were women forced into it?

Nicolas Poussin, A Bacchanalian Revel before a Term, 1632-3, National Gallery, London

I have a feeling that the Maenads or Baccantes (generally considered a Roman word for Maenad) in Poussin’s work are fine. I feel we are at the start of proceedings here with a bit of light dancing in front of the statue or ‘term’ of Pan the god of the wild whose name also means ‘everything’ but came to be associated with lust. Forced into it? Not these ones…

P.S. What’s the difference between a nymph and a maenad? Nymphs weren’t mortal but mythological creatures who helped raise Dionysus and honoured him willingly and without getting falling-over pissed.

The video of this episode can be viewed here. To view the entire ‘Elevenses with Lynne’ archive, head to the Free Art Videos page.