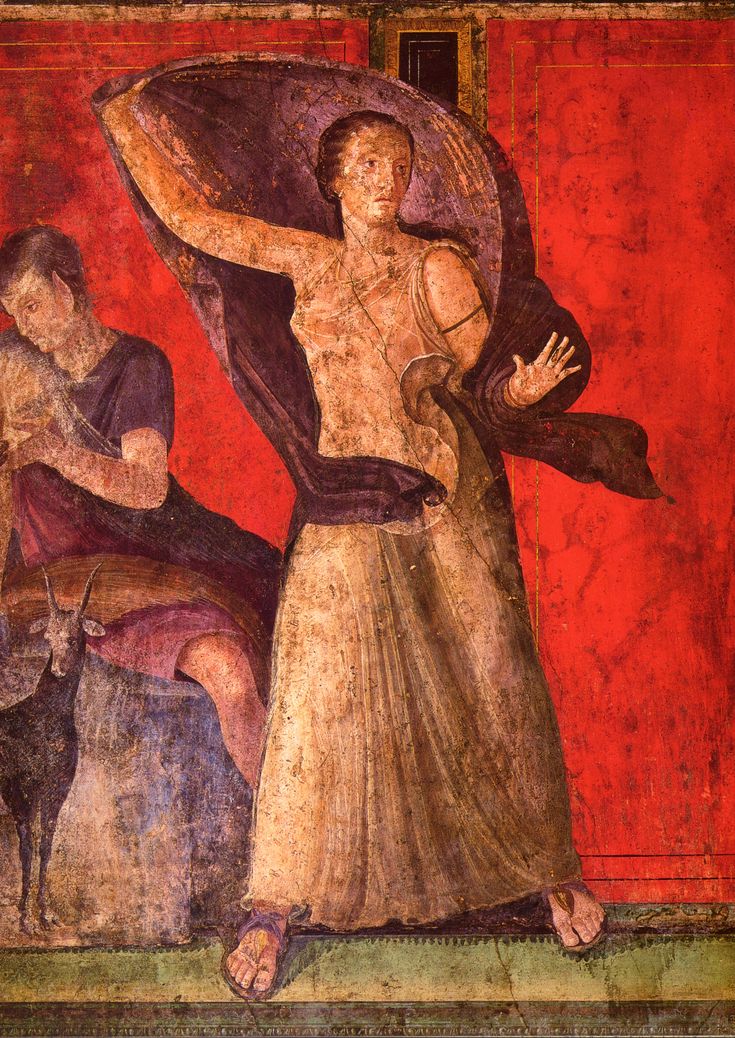

Those of you who haven’t caught me live on Instagram (yet!) might not know that there is almost always a shout out for GORE. So here we are at the start of a veritable gorefest. This fresco of poor St Stephen is a mere warm up to some of the other frescos in the same series that I’m going to show you over the coming weeks…you have been warned! Spoiler alert: it’s not very festive!!

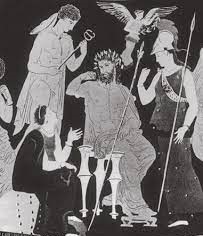

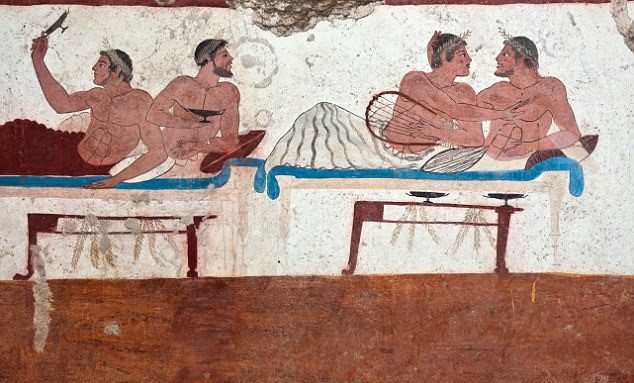

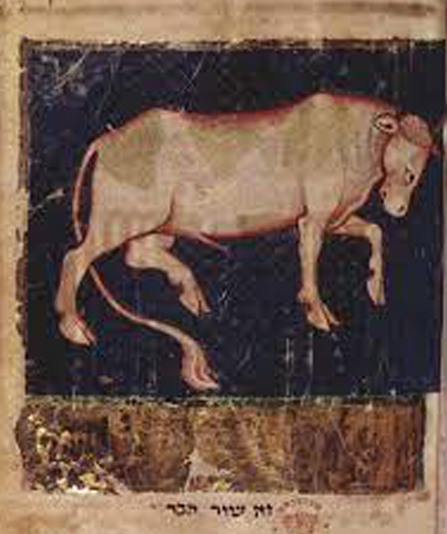

St Stephen was the first person to be martyred in the name of Christianity. He’s kneeling in his red robe arms held out to his sides, perhaps in a nod to Christ’s crucifixion, eyes to the heavens as he’s pelted at point blank range with stones, or possibly baked potatoes.

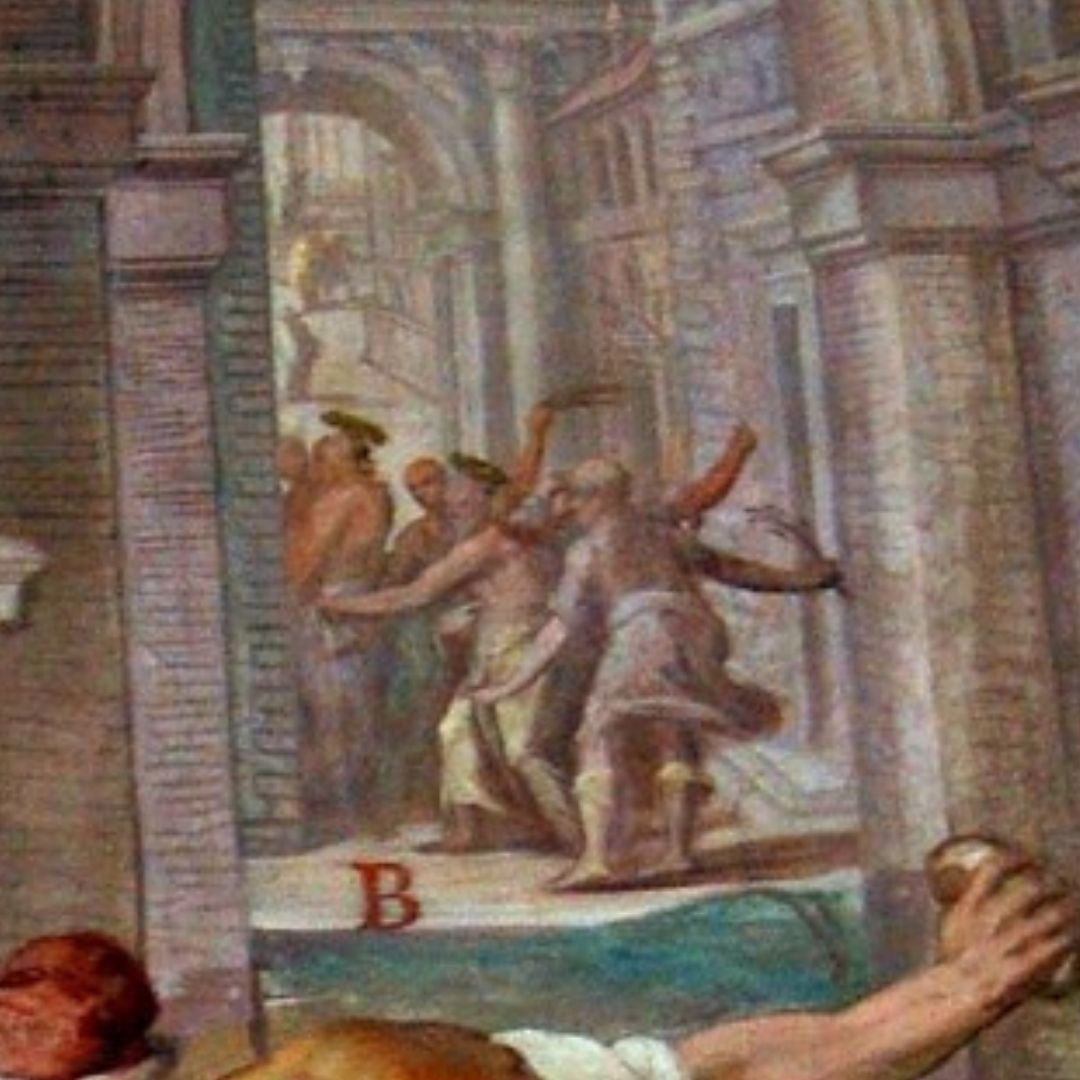

N. Circignani and M. da Siena, The Martyrdom of St Stephen, Santo Stefano Rotondo, 1581-2

St Stephen, however, doesn’t seem to care much and nor does he seem to have noticed the vision of Christ and God in the cloud above which was what partially got him into trouble in the first place. St Stephen was a brilliant orator and held a lot of views that went against public opinion so when, in a court of law in Jerusalem, he claimed that Jesus’s death was murder, that Moses had foretold of Christ’s coming and that he could, by the way, see a vision in the sky of Christ standing at God’s right hand, things went badly. St Stephen was chased out of the court by an angry mob and stoned to death for his beliefs.

In the background to the right we have a group that the artist identifies with a ‘B’ as the apostles (there’s a guide to the lettering below the fresco). I imagine that this is a reference to the 12 apostles being dispersed, metaphorically if not geographically, after Stephen’s death because you can see some figures with halos being harangued by others brandishing branches.

Over to the left in the background is a man identified as Jacobus. He’s about to get beheaded. I think this could be James the Great who was the first of the apostles to be martyred and he did, according to the New Testament, get his head chopped off.

I’m not convinced, however, looking at the architecture, that this scene is representative of Jerusalem in the 1st century A.D. There is a reason for that. The artist, Niccolo Circignani, was more than likely asked to present Rome as the successor to Jerusalem. These frescoes were painted in 1582 at the height of the Counter Reformation so glorifying Rome and Catholicism was important.

And the catalogue of bodily horrors in the name of martyrdom that this fresco cycle represents was clearly part of that.

Yes, St Stephen is one of the least gruesome images in the series. For an idea of what’s to come, here’s a description by Charles Dickens. He didn’t mince his words when he wrote about the works in Pictures from Italy, published in 1846:

… St. Stefano Rotondo a damp, mildewed vault of an old church in the outskirts of Rome, will always struggle uppermost in my mind, by reason of the hideous paintings with which its walls are covered. These represent the martyrdoms of saints and early Christians; and such a panorama of horror and butchery no man could imagine in his sleep, though he were to eat a whole pig raw, for supper. Grey-bearded men being boiled, fried, grilled, crimped, singed, eaten by wild beasts, worried by dogs, buried alive, torn asunder by horses, chopped up small with hatchets: women having their breasts torn with iron pinchers, their tongues cut out, their ears screwed off, their jaws broken, their bodies stretched upon the rack, or skinned upon the stake, or crackled up and melted in the fire: these are among the mildest subjects. So insisted on, and laboured at, besides, that every sufferer gives you the same occasion for wonder as poor old Duncan awoke, in Lady Macbeth, when she marvelled at his having so much blood in him.

The video of this episode can be viewed here. Or at least partially viewed as there was a technical difficulty and I was interrupted in full flow! To view the entire ‘Elevenses with Lynne’ archive, head to the Free Art Videos page.

Recent Comments