Today we are between a rock and a hard place, so to speak. In times past folks may have been more worried about being between Scylla and Charybdis which, to be honest, is a pretty terrible place to be as anyone who has ever passed through the Straits of Messina between Italy and Sicily will know.

Who or what are Scylla and Charybdis?

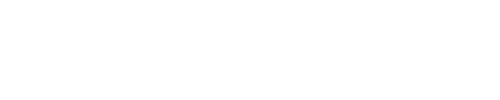

This is a fresco from a cycle of works about Ulysses or Odysseus who had the journey of all journeys home from Troy, and as part of this nightmare had to pass through the Straits of Messina.

Alessandro Allori, Scylla from the Ulysses Cycle, 1575, Palazzo Salviati, Florence

Charybdis is depicted on the bottom right of the fresco and was thought to be the daughter of Poseidon, the Sea God, and Gaia, the Earth Goddess, which is funny because I always thought of her as a man; she definitely looks like an old man here.

As with many stories in Greek mythology, Charybdis had a better start in life which, thanks to Zeus, has now somewhat gone down the drain.

Being the daughter of Poseidon, she was closer to him than she was to her uncle Zeus and so when Poseidon requested that she help him increase the size of his realm by flooding large areas of land with seawater, she acquiesced only to incur the wrath of Zeus. No one wants the wrath of Zeus because he’s nothing if not inventive. As Charybdis’s punishment, she was turned into a monster that would eternally swallow sea water, creating whirlpools.

Scylla may have had an even more dramatic and terrible transformation as she was a beautiful nymph, possibly or possibly not the daughter of Lamia, who got herself turned into a terrible monster, destined to be trapped in the rocks opposite Charybdis. Her monstrosity took the form of six ravenous heads that yapped like dogs and had three rows of sharp teeth to tear apart any sailor that came within reach. Unfortunately, six of Odysseus’s men were lost to her as we see here. You have to love the fact that the remaining men simply seem mildly curious at the fate of their fellow sailors.

The Strait of Messina is, by the way, extremely dangerous so who knows, perhaps the legends were created to fit the geography rather than the other way round?! Controversial!

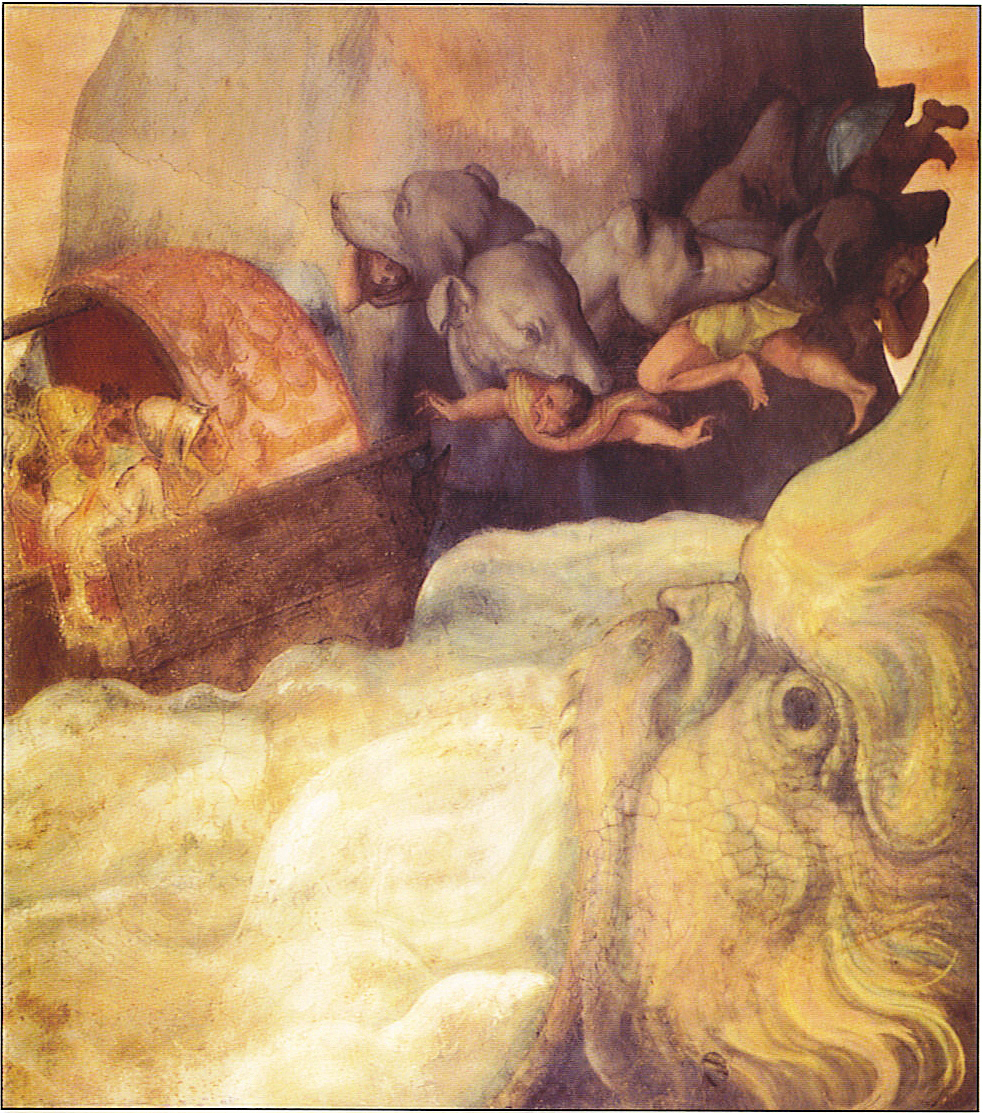

Here Scylla is again on this krater from classical antiquity. I’m not sure those dogs look particularly terrifying?! It’s curious that she has a serpentine tail and carries a fish knife. Arguably depictions of her altered after Ovid’s Metamorphosis became widely known and most artists took their cue from his description:

She frantically felt for the flesh of her thighs, her legs and her feet,

but all that she found was a cluster of gaping hell-hounds.

She’d nothing to stand on but rabid dogs whose bestial backs she was holding

in check beneath her truncated loins and protuberant belly (trans. David Raeburn)

Krater from Classical period, circa 450-425BC, Louvre, Paris

Let’s go back to the story of Scylla because you would imagine that she must have done something truly horrific to have such a grim destiny.

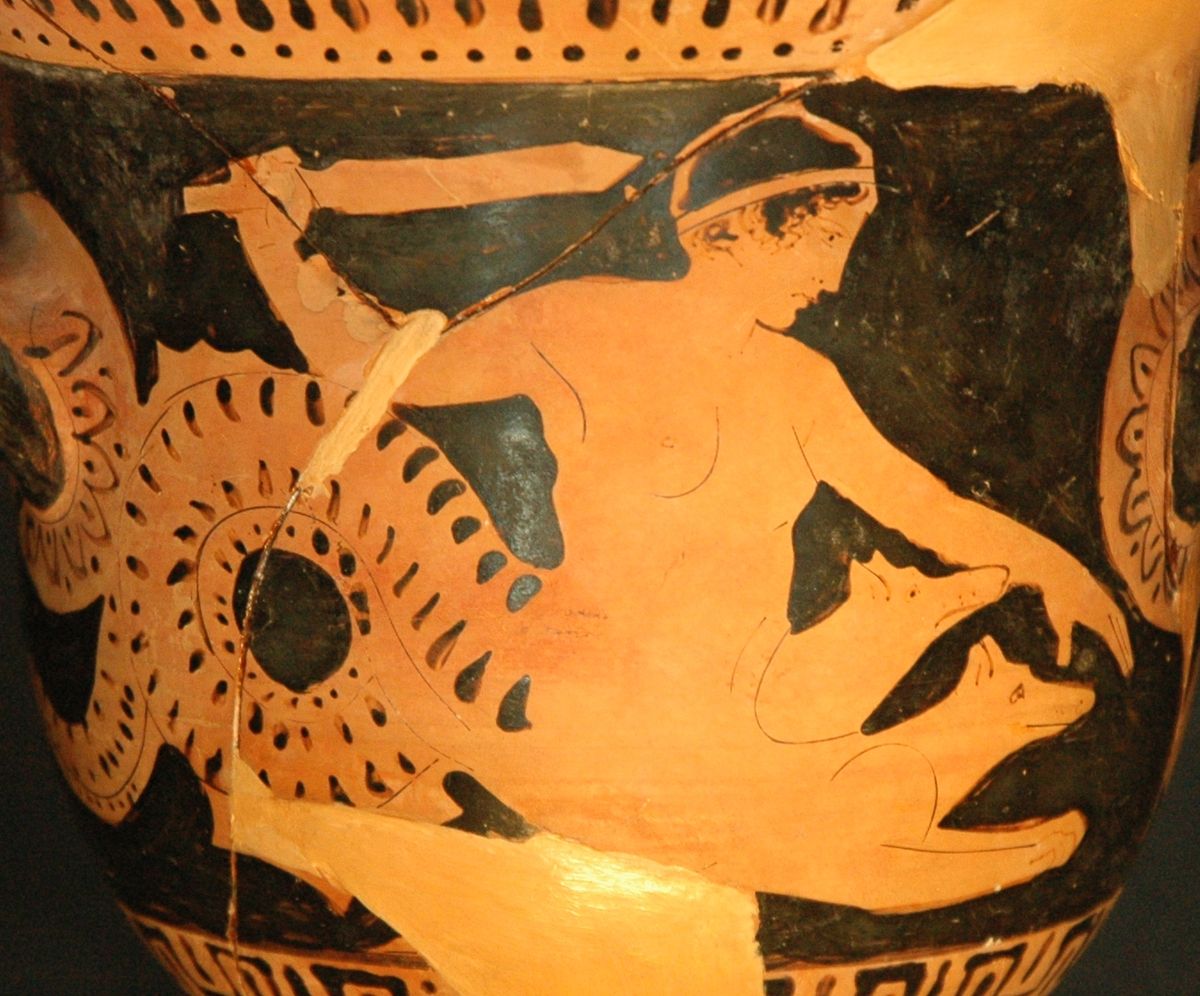

The truth is that she did absolutely nothing wrong except attract the wrong man. Here he is. This is Glaucus, at least as Rubens imagined him, and I find it very hard to believe that Scylla wasn’t interested but she wasn’t.

Glaucus was extremely interested in her, however, oh yes! So much so that he went to the witch Circe to ask her make him a love potion to give to Scylla. But what does Circe do instead? She gives him a draft that turns Scylla into a monster. Why? Because Glaucus is irresistible to at least one lady in this story! Circe doesn’t get her man, however, she gets exiled instead and wreaks havoc elsewhere.

Circe isn’t in this image but here is the lovely Scylla who looks as though she’s just taken all her unruly dogs for a walk by the sea wearing only a transparent wisp of material and hopefully a lot of SPF 50. The model was Rubens’ second wife Helen Fourment who was 37 years his junior and to his evident delight, very happy to pose nude.

Rubens, Scylla and Glaucus, 1636, Musée Bonnat-Hellau, France

If we know what Rubens’ main concern was (he painted Helen as often as he could and absolutely adored her), Turner’s is also obvious. Same scene, completely different focus! Look at that sun – the light is just fantastic as you would expect from Turner. BUT although we know that he excelled at painting dramatic light effects, the sun is sort of part of the story. Guess who Circe’s father was? Helios the Sun God. Circe’s presence can be said, therefore, to radiate throughout this work. Apparently, although it’s square, it was also intended to be framed in a circular frame making the reference to the sun even more implicit. This was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1841 where it was ridiculed for being indistinct and lacking detail.

J. M. W. Turner, Scylla and Glaucus, 1841, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

The video of this episode can be viewed here. To view the entire ‘Elevenses with Lynne’ archive, head to the Free Art Videos page.