Today we’re talking about an emoji.

It’s probably one of my most frequently used emoji’s too so what does that say about me? Maybe not that I’m constantly in fear, but the painting that it derives directly from is absolutely a universal symbol of anxiety.

It’s a painting that doesn’t need much introduction. It’s almost as famous as the Mona Lisa. It’s Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

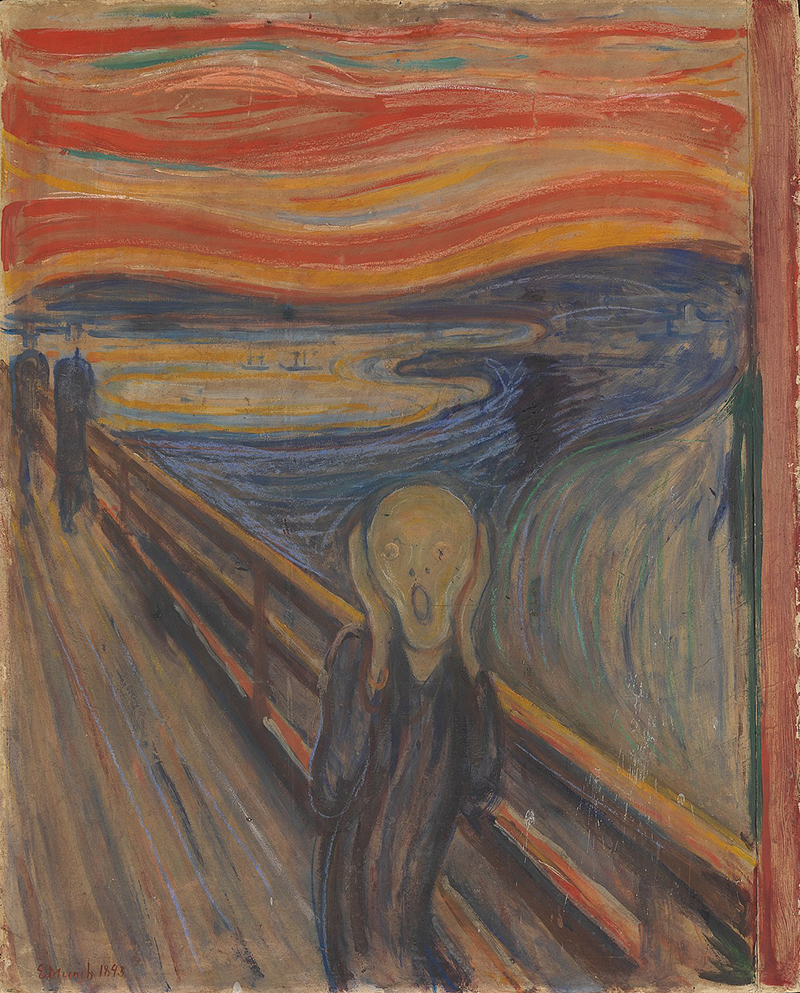

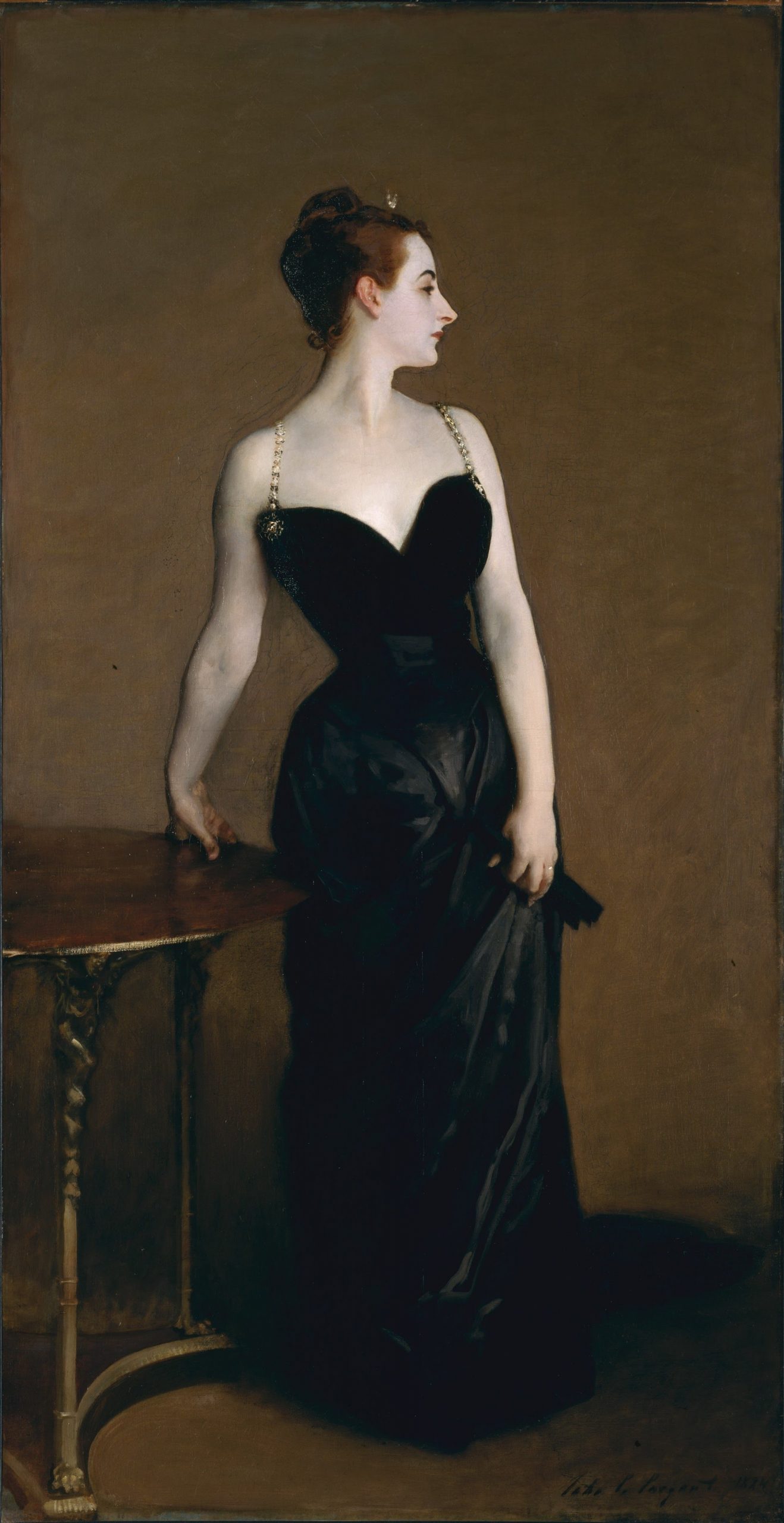

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893, National Gallery, Oslo, Norway

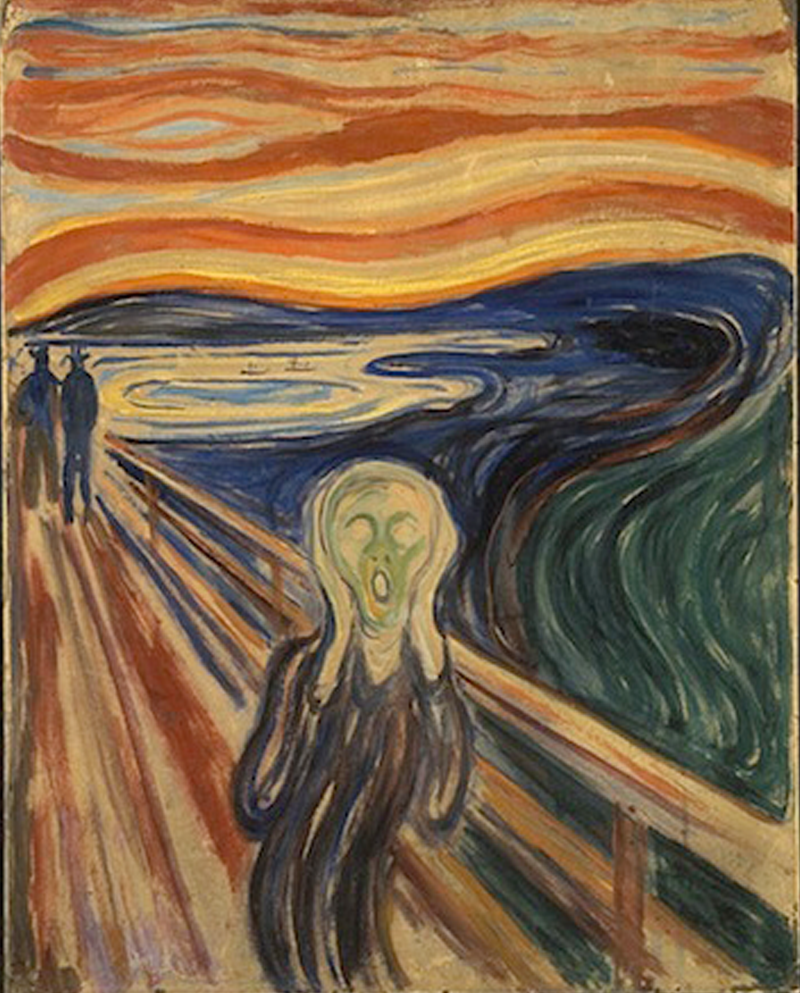

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1910, Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway

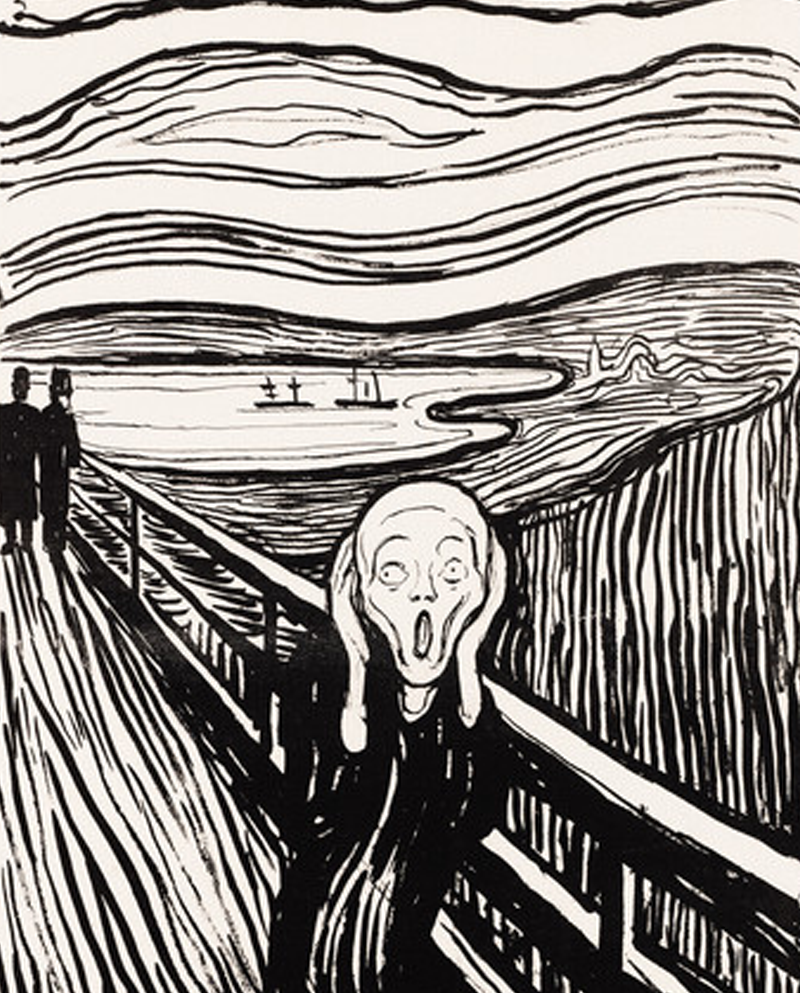

Edvard Munch, Lithograph of The Scream

Thing is that there isn’t just one Scream but 4 plus a lithograph so that he could create black and white prints. There’s a painted version and a crayon version from 1893, a pastel version from 1895 and a later painted version from 1910.

It is a pretty compelling image largely because it’s quite simple.

The bridge creates some spatial recession and along with the two figures in the background it’s a straight line in a world of swirls. The lake or fjord beneath the bridge merges into the shoreline to the right and to hills and then sky above; this part of the painting is really flat which makes it ambiguous, just as the ‘screaming’ figure in the foreground is shrouded in ambiguity. Gender, age, even ethnicity are unarticulated which it what makes this figure so universally captivating. It’s nobody and everybody.

Returning to the composition, it’s interesting that this figure is different to the people in the background – there are no straight lines here – it blends far more easily into the swirls of nature; the sky, fjord and landscape. This was Munch’s intention. The figure probably isn’t screaming but was trying to block out a (possibly much more terrifying) ‘scream of nature’. Munch did write that The Scream was a work about remembered sensation and as such it may be recalling the extraordinary blood red sunsets from a decade previously which were caused by an eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia. He wrote that he had been walking with a couple of friends when the sky seemed to engulf the landscape in flames, triggering an unnerving sense of fear in him. The original name of the piece translates as The Scream of Nature which was a phrase he used in a poem describing the event.

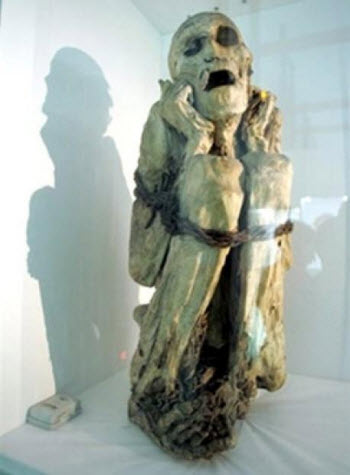

Chachapoya mummy, 16th century, Musee de l’Homme, Paris, France. Photo: Francois Guillot / AFP / Getty Images

He may have also been recalling something that he saw at the 1889 Trocadero exhibition in Paris with Gaugin. This mummy had recently been discovered in Peru. I’m not surprised it stuck in his mind! Is there a resemblance to the painting? I think so.

Analysis showed that in life the mummy had been male and was shot in the back in the mid-16th century.

That said, some scholars think that it could also be about suicide. The bridge depicted was a known spot for jumpers and it’s near a slaughterhouse and the asylum that housed Munch’s schizophrenic sister. He was terrified of developing the mental illness that ran through his family, plus at the time he created the first images of The Scream, he was broke financially and heart-broken from a failed love affair.

I’m not so convinced about the ‘suicide’ interpretation although a tiny pencil inscription on the top left corner of the 1893 version has added fuel to theory. It reads “Can only have been painted by a madman” and has now been attributed to Munch himself, apparently scrawled after a meeting with a medical student who commented that that the painting must be the work of a disturbed mind.

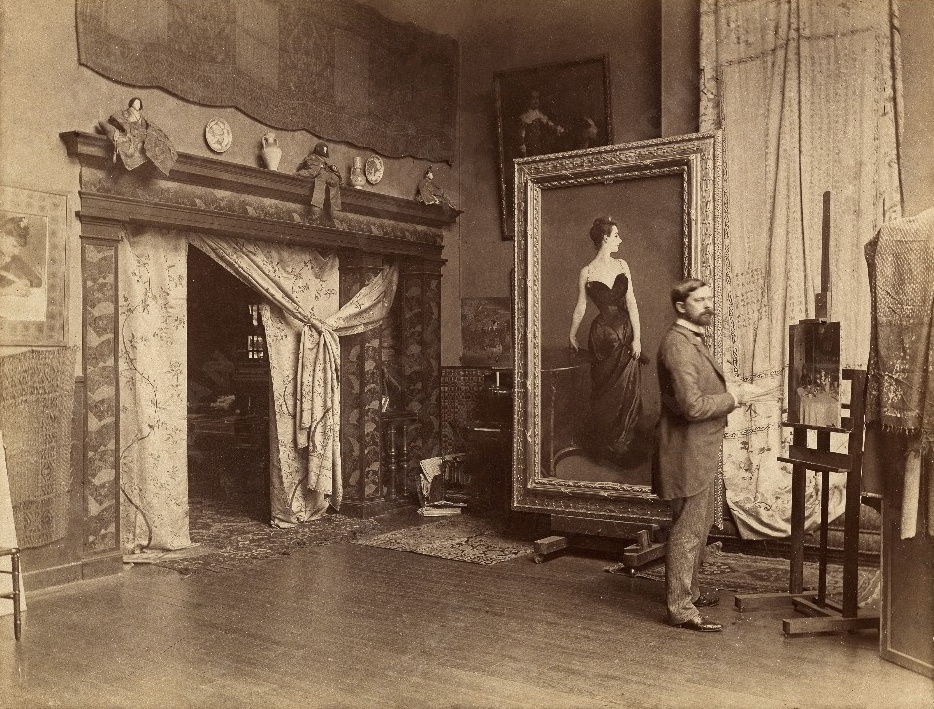

Arguably it’s disturbed minds that have led to The Scream being stolen twice! Well, the painted versions have each been stolen once.

The first theft was in 1994 on the day that the Winter Olympics opened in Lillehammer. Unbelievably all the thieves had to do was pop a ladder up to a window of the National Gallery in Oslo, to climb inside and make off with the 1893 painting. They were so pleased with the ease of this crime that they added insult to robbery, leaving a note that read, “Thanks for the poor security.” Thankfully, the painting was recovered within three months.

Then in 2004 it was the turn of the 1910 version. There was rather more drama this time. In a daring daytime heist, two masked men armed with guns stole The Scream and Munch’s Madonna from Oslo’s Munch Museum. The thieves were caught and convicted fairly rapidly but a couple of years later, the paintings were still missing despite a hefty reward.

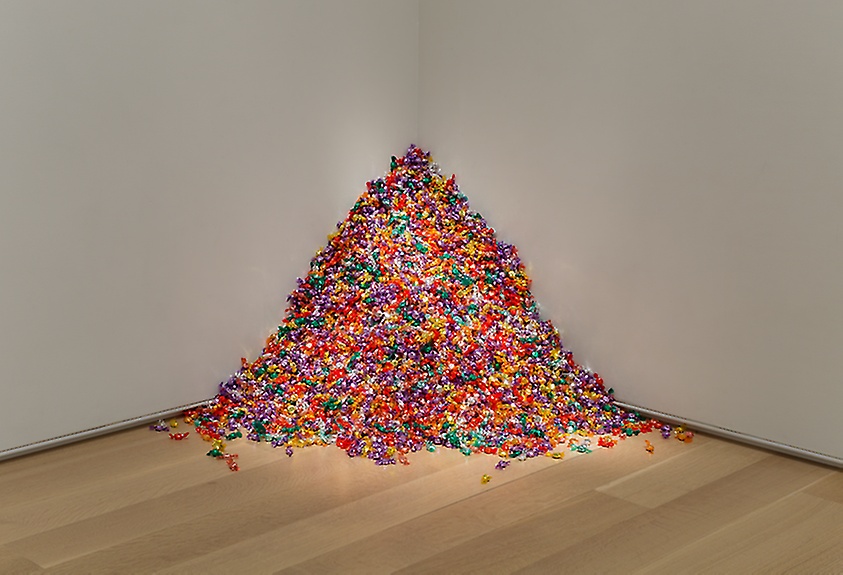

Any guesses as to how the paintings were finally recovered? The plan involved 2 million dark chocolate M&Ms.

Basically Mars came up with a marketing ploy that turned out to be a work of genius. They ran an advert of a red M&M playing hopscotch with the painting and offered a reward of 2 million dark chocolate M&Ms for information.

It only took a few days for a convict with a penchant for the sweets to come forward with information on the works’ whereabouts in exchange for conjugal visits and the 2.2 tons of M&Ms.

He didn’t get what he wanted but the cash value of almost £20k went to the Munch Museum.

Of course The Scream has provided inspiration for many a media mogul.

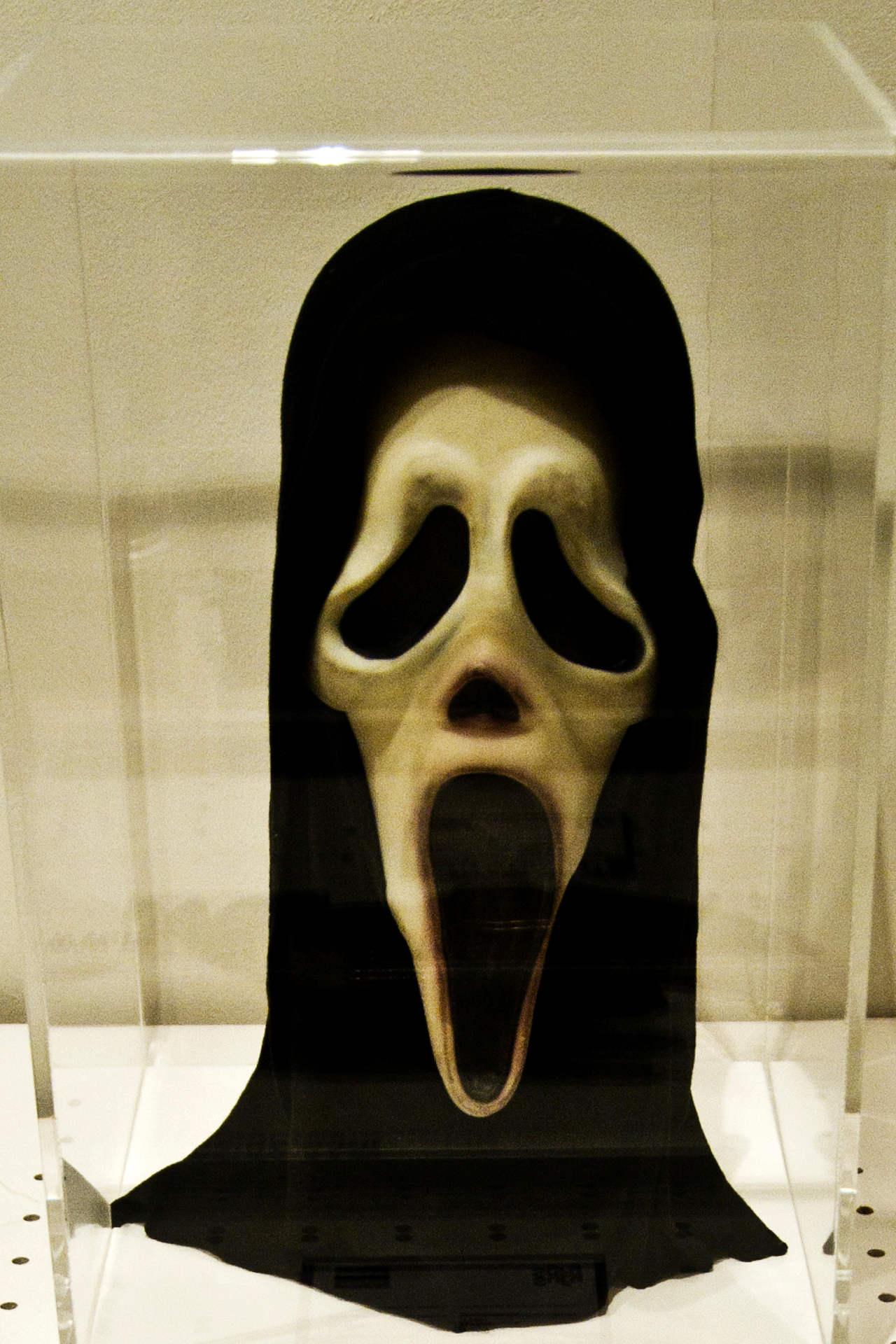

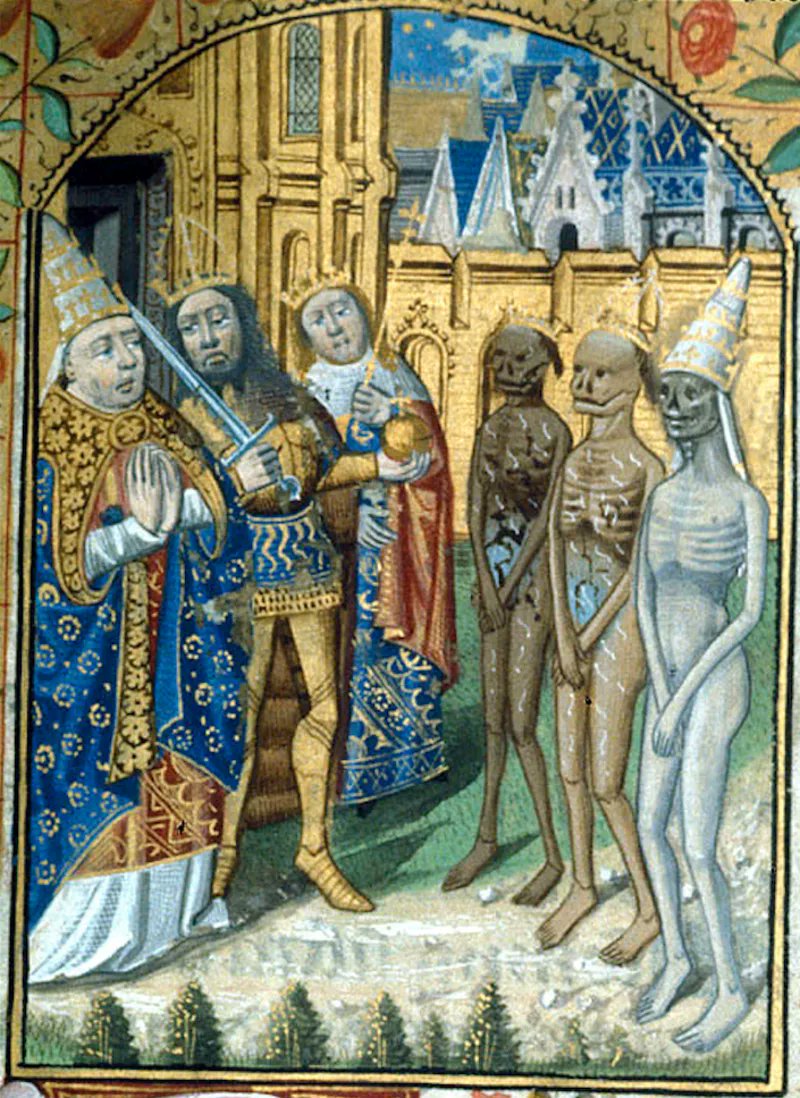

I give you Macauly Caulkin’s famous scream in Home Alone; the aliens known as the Silence in Dr Who (back to aliens!) and most terrifying of all, the mask in Wes Craven’s Scream movies. Whooooa!!!

‘The Silence’ from Doctor Who

The mask from Scream

The video of this episode can be viewed here. To view the entire ‘Elevenses with Lynne’ archive, head to the Free Art Videos page.

Recent Comments